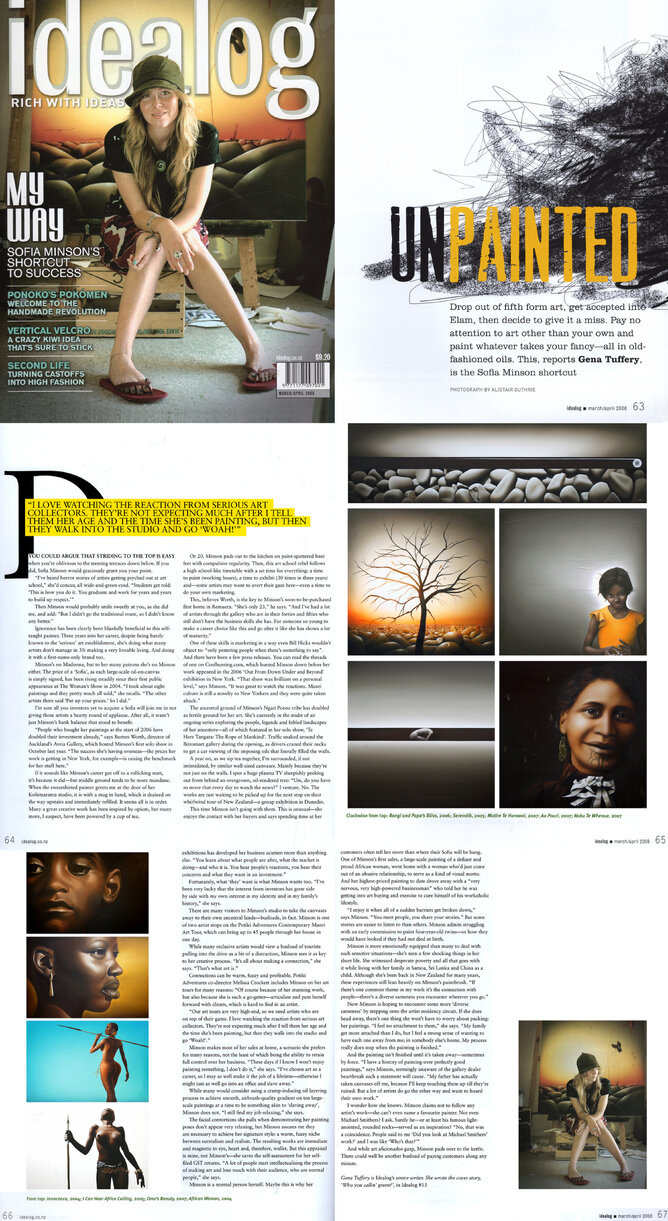

ldealog Magazine

March/April 2008

Front cover and feature article featuring Sofia Minson Pg 63 - 67

Photographs by Alistair Guthrie

Article Written by Gena Tuffery

UNPAINTED - MY WAY

SOFIA MINSON’S SHORTCUT TO SUCCESS

Drop out of fifth form art, get accepted into Elam, then decide to give it a miss. Pay no attention to art other than your own and paint whatever takes your fancy—all in old fashioned oils. This, reports Gena Tuffery, is the Sofia Minson shortcut.

YOU COULD ARGUE THAT STRIDING TO THE TOP IS EASY when you're oblivious to the teeming terraces down below. If you did, Sofia Minson would graciously grant you your point.

"I've heard horror stories of artists getting psyched out at art school,” she‘d concur, all wide-and-green-eyed. “Students get told: ‘This is how you do it. You graduate and work for years and years to build up respect.’"

Then Minson would probably smile sweetly at you, as she did me, and add: “But I didn‘t go the traditional route, so I didn't know any better.”

Ignorance has bccn clearly been blissfully beneficial to this self-taught painter. Three years into her career, despite being barely known to the 'serious‘ art establishment, she‘s doing what many artists don‘t manage in 30: making a very liveable living. And doing it with a first-name-only brand too.

Minson's no Madonna, but to her many patrons she’s no Minson either. The price of a ‘Sofia’, as each large-scale oil-on-canvas is simply signed, has been rising steadily since their first public appearance at The Woman's Show in 2004. "I took about eight paintings and they pretty much all sold,” she recalls. “The other artists there said ‘Put up your prices.’ So I did.

“I’m sure all you investors yet to acquire a Sofia will join me in not giving those artists a hearty round of applause. After all, it wasn't just Minson’s bank balance that stood to benefit.

“People who bought her paintings at the start of 2006 have doubled their investment already." says Burton Worth, director of Auckland's Aveia Gallery, which hosted Minson’s first solo show in October last year. "The success she’s having overseas—the prices her work is getting in New York, for example—is raising the benchmark for her stuff here.”

If it sounds like Minson‘s career got off to a rollicking start, it‘s because it did—but middle ground tends to be more mundane. When the sweatshirted painter greets me at the door of her Kohimarama studio, it is with a mug in hand, which is drained on the way upstairs and immediately refilled. It seems all is in order. Many a great creative work has been inspired by opium, but many more, I suspect, have been powered by a cup of tea. Or 20. Minson pads out to the kitchen on paint-spattered bare feet with compulsive regularity. Then, this art school rebel follows a high school-like timetable with a set time for everything: a time to paint (working hours), a time to exhibit (30 times in three years) and—some artists may want to avert their gaze here—even a time to do your own marketing.

This, believes Worth, is the key to Minson‘s soon-to-be-purchased first home in Remuera. “She‘s only 23." he says. “And I've had a lot of artists through the gallery who are in their forties and fifties who still don't have the business skills she has. For someone so young to make a career choice like this and go after it like she has shows a lot of maturity."

One of these skills is marketing in a way even Bill Hicks wouldn't object to: “only pestering people when there's something to say”. And there have been a few press releases. You can read the threads of one on Coolhunting.com, which hunted Minson down before her work appeared in the 2006 ‘Out From Down Under and Beyond’ exhibition in New York. “That show was brilliant on a personal says Minson. “It was great to watch the reactions. Maori culture is still a novelty to New Yorkers and they were quite taken aback.

“The ancestral ground of Minson‘s Ngati Porou tribe has doubled as fertile ground for her art. She's currently in the midst of an ongoing series exploring the people, legends and fabled landscapes of her ancestors—all of which featured in her solo show, ‘Te Here Tangata: The Rope of Mankind'. Traffic snaked around the Britomart gallery during the opening, as drivers craned necks to get a car viewing of the imposing oils that literally filled the walls.

A year on, as we sip tea together, I'm surrounded, if not intimidated, by similar wall-sized canvases. Mainly because they‘re not just on the walls. I spot a huge plasma TV sheepishly peeking out from behind an overgrown, oil-rendered tree: “Um, do you have to move that every day to watch the news?“ I venture. No. The works are just waiting to picked up for the next stop on their whirlwind tour of New Zealand—a group exhibition in Dunedin.

This time Minson isn’t going with them. This is unusual—she enjoys the contact with her buyers and says spending time at her exhibitions has developed her business acumen more than anything else. “You learn about what people are after, what the market is doing—and who it is. You hear people's reactions, you hear their concerns and what they want in an investment."

Fortunately, what ‘they’ want is what Minson wants too. “I‘ve been very lucky that the interest from investors has gone side by side with my own interest in my identity and in my family‘s history,“ she says.

There are many visitors to Minson‘s studio to take the canvases away to their own ancestral lands—busloads, in fact. Minson is one of two artist stops on the Potiki Adventures Contemporary Maori Art Tour, which can bring up to 45 people through her house in one day.

While many reclusive artists would view a busload of tourists pulling into the drive as a bit of a distraction. Minson sees it as key to her creative process. "It's all about making a connection,” she says. “That's what art is."

Connections can be warm, fuzzy and profitable. Potiki Adventures co-director Melissa Crockett includes Minson on her art tours for many reasons: "Of course because of her stunning work, but also because she is such a go-getter—articulate and puts herself forward with clients, which is hard to find in an artist.

“Our art tours are very high-end, so we need artists who are on top of their game. I love watching the reaction from serious art collectors. They're not expecting much after I tell them her age and the time she‘s been painting, but then they walk into the studio and go ‘Woah!’.”

Minson makes most of her sales at home, a scenario she prefers for many reasons, not the least of which being the ability to retain full control over her business. “These days if I know I won‘t enioy painting something, I don’t do it,” she says. “I've chosen art as a career, so I may as well make it the job of a lifetime—otherwise I might just as well go into an office and slave away."

While many would consider using a cramp-inducing oil layering process to achieve smooth. airbrush-quality gradient on ten largescalce paintings at a time be something akin to ‘slaving away’ Minson does not. "I still find my job relaxing,” she says.

The facial contortions she pulls when demonstrating her painting posts don‘t appear very relaxing, but Minson assures me they are necessary to achieve her signature style: a warm, fuzzy niche between surrealism and realism. The resulting works are immediate and magnetic to eye, heart and, therefore, wallet. But this appraisal is mine, not Minson‘s—she saves the self-assessment for her self-filed GST returns. “A lot of people start intellectualising the process of making art and lose touch with their audience, who are normal people,” she says.

Minson is a normal person herself. Maybe this is why hervcustomers often tell her more than where their ‘Sofia’ will be hung. One of Minson's first sales, a large-scale painting of a defiant and proud African woman, went home with a woman who’d just come out of an abusive relationship, to serve as a kind of visual motto. And her highest-priced painting to date drove away with a “very nervous, very high-powered businessman“ who told her he was getting into art buying and exercise to cure himself of his workaholic lifestyle.

“I enjoy it when all of a sudden barriers get broken down," says Minson. “You meet people, you share your stories." But some stories are easier to listen to than others. Minson admits struggling with an early commission to paint four-year-old twins—or how they would have looked if they had not died at birth.

Minson is more emotionally equipped than many to deal with such sensitive situations—she‘s seen a few shocking things in her short life. She witnessed desperate poverty and all that goes with it while living with her family in Samoa, Sri Lanka and China as a child. Although she‘s been back in New Zealand for many years, these experiences still lean heavily on Minson’s paintbrush. “If there's one common theme in my work it's the connection with people—there's a diverse sameness you encounter wherever you go.“

Now Minson is hoping to encounter some more ‘diverse sameness’ by stepping onto the artist residency circuit. If she does head away, there's one thing she won‘t have to worry about packing: her paintings. “I feel no attachment to them,” she says. “My family get more attached than I do, but I feel a strong sense of wanting to have each one away from me; in somebody else’s home. My process really does stop when the painting is finished.”

And the painting isn't finished until it's taken away—sometimes by force. “I have a history of painting over perfectly good paintings,” says Minson, seemingly unaware of the gallery dealer heartbreak such a statement will cause. “My father has actually taken canvases off me, because I‘ll keep touching them up till they‘re ruined. But a lot of artists do go the other way and want to hoard their own work.“

I wonder how she knows. Minson claims not to follow any artist‘s work—she can't even name a favourite painter. Not even Michael Smithers? I ask. Surely he—or at least his famous light-anointed, rounded rocks—served as an inspiration? “No, that was a coincidence. People said to me “Did you look at Michael Smithers' work." and I was like "Who's that?"

And while art aficionados gasp. Minson pads over to the kettle. There could well be another busload of paying customers along any minute.

Gena Tuffery is Idealog’s senior writer. She wrote the cover story, 'Who you callin' green?', in ldealog #13

Posted by artist Sofia Minson from NewZealandArtwork.com

New Zealand Maori portrait and landscape oil paintings